One of the central precedents in our course is the idea of the 'design process'. This is something widely discussed in the design community, and to us it is presented mainly in the form of the 'double diamond' or '4D's':

The 4D's are a central part of our course structure, and may be key next year as the open final year structure is based on this concept. In third year, a group project I worked on,

terry, used a structure similar to this, although we swapped ideas during the generation stage in order to de-personalise design concepts.

It is often used as a tool by design consultancies, as a clean and understandable way of communicating with clients about where exaclty they are in any stage of a given project.

Sometimes thinly veiled using slightly different words.

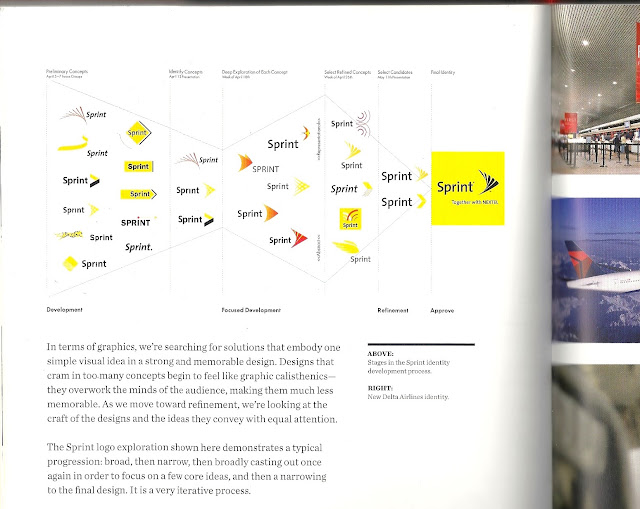

We also see this idea propagated in design books, such as Essential Principles of Graphic Design by Debbie Millman.

The central idea here is that design is shown to be a linear process, with an added dimension which suggests that concepts should be 'expanded' into multiple versions of specific starting points. It is this expansion which is the primary creative vehicle, attempting to force random inspiration into the process. Graphically, this linear process could be shown on a graph as such:

The two main projects I did this year in my fourth year have been an opportunity to revisit the idea of design process, and I have done these two projects in quite different ways. The first, the shop project, which yielded an expensive metal fidget spinner, the Puck, as it's result, was what I will call a 'pick and finish' project:

I chose a pre-conceived concept straight away, and just began it's delivery. This was important for this project in particular, as the required deliverables were 11 fully finished products, so the focus for me was on ironing out the manufacturing process details and difficulties.

My second main project, which focused on 'water delivery in the home' went something like this:

The original intent was for it to be a 'Rapid Throwaway Prototype' design process, where the full length of the project was explored as an intense process in the first week, before going back over to re-consider the decisions were made. It actually became more of an 'iterative' approach, where I went though several exploration stages and several development stages. This was beneficial in two ways:

The deliverables were less material than in the 'puck' project, so I could afford to explore ideas in a more conceptual way, and by continually realising them in 'full resolution' it was easy to get feedback from potential users.

In getting deep into technical depth very early on in the project, I was conscious of minute difficulties such as plumbing thread sizes, household water systems and sink hole dimensions throughout the project, which fed into the design as a whole and meant that I could deliver whatever it was in a short time without hitting too may technical hurdles. Additionally, n having no respect for my current 'idea' I was also willing to throw it away as soon as another idea came along, constantly adopting whatever the evidence pointed to as the current 'best', no work was wasted however, because the insights were carried over.

Why the double diamond is a myth

Can ideas be 'generated'?

Linear design processes feature an initial research stage, followed by a using of any insights gathered in order to inform concepts. The primary feature of this is in 'expansion'. Many a design consultancy website will show a large creative looking spread of post-its and brainstorms, as the team comes together to turn their carefully picked out insights into brand new ideas. The sky is the limit. IDEO are masters at this.

There are some issues however.

Why spend one or two weeks coming up with an exhaustive number of ideas, to then throw them away? The contraction phase of the project, In my experience, often leads to one just choosing the idea they always liked.

Why spend one or two weeks coming up with an exhaustive number of ideas, when you could be spending all the time coming up with ideas? Granted, this is what one does anyway, but the 'model' process should at least take this into account.

Most good ideas already exist. And by that I do not mean that they are on the market and selling in the millions, but most of the last 10 years of innovation milestones have not come from a quick thursday afternoon post-it session, but are things like the iPhone, iPad, electric car and social media, which in some latent, sci-fi sense always existed, they were just waiting for people, technology and the economy to 'deliver' them.

I think the reality of idea generation is that we are really looking for random inspiration, and finding some systematic way of assuring that. So one good idea is to do some deep initial research on a given subject, and hope something pops out to you that hadn't occurred to anyone else before. But this approach is not per se any better way of finding random inspiration than doing, say 15 mini-projects, going on a three month travelling trip, or going to a zen retreat.

Uncertainties Rule

One problem that designers and, later, engineers find is that on a given project, each jump forward also yields a massive leap back, as assumptions made in the prior stage are shattered by new findings. The 'grim technical realities' take hold.

Some ideas, such as Phoneblocks, which became google project Ara, went viral too fast. While an impressive example of a minimal design becoming an expression of a pure conceptual whole, it was merely a icon for the idea of a modular phone and nothing more.

The grim technical reality is that for a number of reasons (motherboard bottlenecking being the most prominent) it is not as simple as it looks in implementation, so Phoneblocks sits happy as a well-rendered and iconic suggestion of a future unlikely to ever happen. The design becomes yet another peice of design media, destined to be just that.

Other ideas are simply watered down for delivery. We see this often in car design, where we are offered a 'peek into' the design process to see a fantastical concept car, which are often only interesting in the degree that they are infeasible.

Usually what happens next is all the interesting stuff gets taken off by the engineers in the delivery stage and we are given the same old car in a new shell, although this is being challenged by the likes of tesla (who don't seem to subscribe to the double diamond methodology).

What is interesting is that the uncertainties don't stop when a product is released. Some ideas like the apple TV and, I may argue, the apple watch, have not properly taken off yet. So they are toyed with and re-evaluated, re-branded maybe in the hopes that they will be revived. Only 56% of new products are successful. (PDMA US Survey 1990,1995,2000) The 4D's doesn't really take this into account, our main problem with it is that in showing the process as specifically two diamonds, it ignores the fact that design is a constantly ongoing and thankless task, instead it prefers to settle at 'deliver' by week 10.

One industry that works in an interesting way in this regard is software, especially the video games industry. Here 'beta testing' and 'early access' are becoming the norm at the expense of fixed, single price releases. Minecraft, one of the most successful video games of the last 10 years was released as a small project and has been continually updated and refined since. How can this influence the way we think about product design?

Design as an intuitive process

Design in it's more 'serious' forms - Corporate R&D, Design Engineering and Consultancy - clearly require certain measurable amounts of accountable progress. Especially those that are beholden to their investors and marketing departments. But a lot of what has really changed things in the last 20 has come from 'headless chickens'- the aforementioned example of Minecraft and 'Notch', the apple computer with Wozniak and Jobs, the world wide web with Tim Berners Lee and Facebook with Mark Zuckerberg.

These were tinkering passion projects that became something bigger than intended, through a useful mixture of dogged determination and of being-in-the-right-place-at-the-right-time. Many of their pioneers found themselves in a favourable position and, with little professional experience, took the right opportunities.

So when we think of who is going to deliver the Next Big Thing, and how it will be delivered, we can almost be sure that it won't be from a giant like IBM, Ford or 3M, but probably from someone tiring away in a garage or in a university dormitory on something pointless. If your design process is organised and accountable, you're doing something wrong.

So why does the myth persist?

Rapid design with throwaway ideas, and the iterative process have recently been beneficial for me. I worked though at least 4 final concepts, before throwing them away and developing something different. At the end though, in my final submission to a rather important client, all that work had to be masked over/ thrown away. An idea is best presented as a Bish-Bash-Bosh of Problem-Insight-Solution, or simply cleanly presented with as little etherial justification as possible. No need to risk sounding unsure about oneself.

Ideas for commercial release need to be very clear and specific in their intention in order to generate investment and to enthuse the public. This clarity may be arrived upon by failing (internally) several times before coming up with something suitable for release, but it must be cleaned up before it is shown to the public. Apple are masters at this.

"So much of the work with the macbook was experimenting with different processes... so many of the products around you want to make you very aware of how clever the solution was...[what we focus on at apple is]...not the terrible struggles that us as designers and engineers had in trying to solve some of the problems"

I think from a marketing perspective, letting consumers too close to what in reality may be an erratic design process, is not just annoying and not interesting, but risks communicating uncertainty. You're better showing off one half-good idea confidently than giving the consumer a choice. This is especially the case in hardware design, where a fixed lump of material is exchanged for a fixed lump of cash in one transaction.

What this means is that even internally in the industry, from tarted-up student design journals, to professional portfolios, to multinational trade fairs, the exciting and productive world of making mistakes and having-no-idea-what-you're-doing is hidden under the carpet. This costs the design world an opportunity to celebrate the world of the mad and creative, but also of the visionary and pragmatic ideas that need to be brute-forced over several years out of solid steel or C#.

***

So is the linear design process, and specifically the double diamond, a myth? Yes and no. Projects do overall need to follow some progression in terms of meeting final aims, so measuring and aiming towards this is a good way of

trying to plan. It is also a useful educational tool, and it probably gives structure to corporate projects where they are otherwise lacking in motivation. That’s probably true, but isn’t a very exciting conclusion. I think in reality design is both less and more complicated than we give it credit for.

There are really, in my opinion (or at least this week's opinion), two centrtal and complimentary components of the 'design process' over any length of time or amount of definition these are:

Realising Inspiration

and

Trial and Error

Realising Inspiration is about finding inspiration (which will more than likely be random), and increasing it's specification and resolution. this is equivalent to the Define and Deliver stages of the double diamond, although I am not suggesting here that there are only two, there could be 50 realisation stages in designing a piece of jewellery, there may be only one in designing a £1.3bn bridge.

Trial and Error is the acceptance of failure as a central component of the design process, in this case, we take out 'realisations' and force them to breaking point. We can do 50 at a time to find the best one, or we can do one at a time and constantly improve upon it. This can be seen in software engineering, as updates are constantly streamed to our devices, but also in more solid objects, such as the commendable Porsche 911 which has seen gentle updates throughout it's astoundingly long life. Dyson actually do have a marketed and presented design process that resembles this, especially the focus on trial and error. The submission page for the James Dyson award specifically asks for it.

My intention here is not necessarily to destroy the double diamond, but to remove it's main flaws - the fact that it relies on 'expansion' over any other kind of random inspiration, and the fact that it is conveniently packaged into whatever length of project that budgets or college timetables require. In reality the specific type of process needed is dependent on what is required from the project. In some cases even, it is interesting to pick a process first, and see what comes out of the other end. It is always enjoyable though. Bring on the next one!