The first post in this series, Modernism, dealt very accurately with the themes and features of Modernism, the philosophy that defined much of the first half of the 20th century. What happened next?

For whatever reason; boredom, restriction or a new cultural awakening, Modernism was replaced by a multitude of differing styles. In the post on Modernism, I defined it using 4 rules:

2) Form

4) The future is

For whatever reason; boredom, restriction or a new cultural awakening, Modernism was replaced by a multitude of differing styles. In the post on Modernism, I defined it using 4 rules:

1) Rules are rules

2) Form follows function

3) Less is more

4) The future is bright

I see what happened after modernism, that is, after the 1960's roughly, that design went into two camps - late modernism and post-modernism. In support of a 'pluralist' theory of styles, I believe that after modernism, what we have is not a single defining style, but a range of different styles. I see late modernism as a refinement or exaggeration of certain specific aspects of modernism, and post-modernism as a rejection thereof. We can construct a picture of both philosophies by considering exaggeration or rejection of the above four rules.

Late Modernism

HSBC Headquarters Norman Foster; Lloyds building, Richard Rodgers; House in Str Tropez, John Pawson; City of arts and sciences, Santaigo Calatrava; Pompidou Centre, Rodgers & Piano; Museo Jumex, David Chipperfield; National Theatre; Barbican Estate; Munich Olympic Stadium, Frei Otto.

What we se here visually is arguably less cohesion and agreement than in the picture of modernism I formed. What we have here is not a single style aiming to continue the utopian dream of modernism. In the real difficulty of merging objectivity, functionality, neutrality & optimism all into one design, late modernists have given up on the wider dream and instead focused on and represented one of these points, usually at the cost of the others.

1) A new objectivity

The modernists believed that rules were rules, often dissolving design theories into simple lists and manifestos. This reflected a belief that truth and human nature were definite things that could be worked out objectively. This manifested itself in square, rigid buildings; useful but technically-minded products and extremely prescriptive urban planning.

Since the seventies, this objective spark has not gone anywhere, but the realisation that structural problems and human nature are more complicated matters than can be solved using only the orthogonal, cartesian plane has elevated the design solutions to a higher, more complex level. Buildings such as the Munich Stadium, designed to some extent by observing the formation of bubbles, still carry the fundamentally modernist belief that the solution is real, definite and specific.

The complex, structural forms epitomised by the architecture of Renzo Piano, Santiago Calatrava, Norman Foster and Nicholas Grimshaw indicate and express complex design parameters, creating a performance of science and technology. This can be impressive, but they can also be rather facetious and tiring examples of self-congradulation. They focus fully on (unnecessary?) objective resolution at the expense of simplicity and clarity.

Kartal Masterplan, Zaha Hadid, Patrik Schumacher

This objective but 'oh so complicated, look how hard we worked' approach finds its culmination in the 'Parametric' designs of Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry, which, despite pretensions of computer generation, probably owe more to artistic vision enabled by a hard working team of CAD monkeys. This is the latest manifestation of 'objectivity' and despite the claim that they are inspired by the likes of Frei Otto, might actually not be modernist or objective at all.

2) Form follows over-exaggerates function

Pompidou Center, Renzo Piano, Richard Rogers and Gianfranco Franchini, 1977

While arguably intelligent modernist design like Gropius' bauhaus building in Dessau and Wagner's Postal Savings Bank moved forward the world of design by omitting ornament and utilising glass and steel, by the 60's this had become the International Style, one that was boring, formulaic and repetitive, especially when done by minor architects not vested with the poetry of Le Corbusier. The solution was reached with the completion of the Pompidou Center in 1979, which is desperate to make a 'punk' statement, but is still reluctantly beholden to the rules of modernism.

It achieves it's objectives by using the functional systems that it is required to have as the ornament itself, proudly displaying them as a sculpture to the rational mind. There are a more than a few contradictions here. There is no real reason to paint the air ducts blue, and i'm sure insulation and security are also hindered, not to mention longevity of the exposed parts. From my experience with it though, it is actually a functional, flexible and open space.

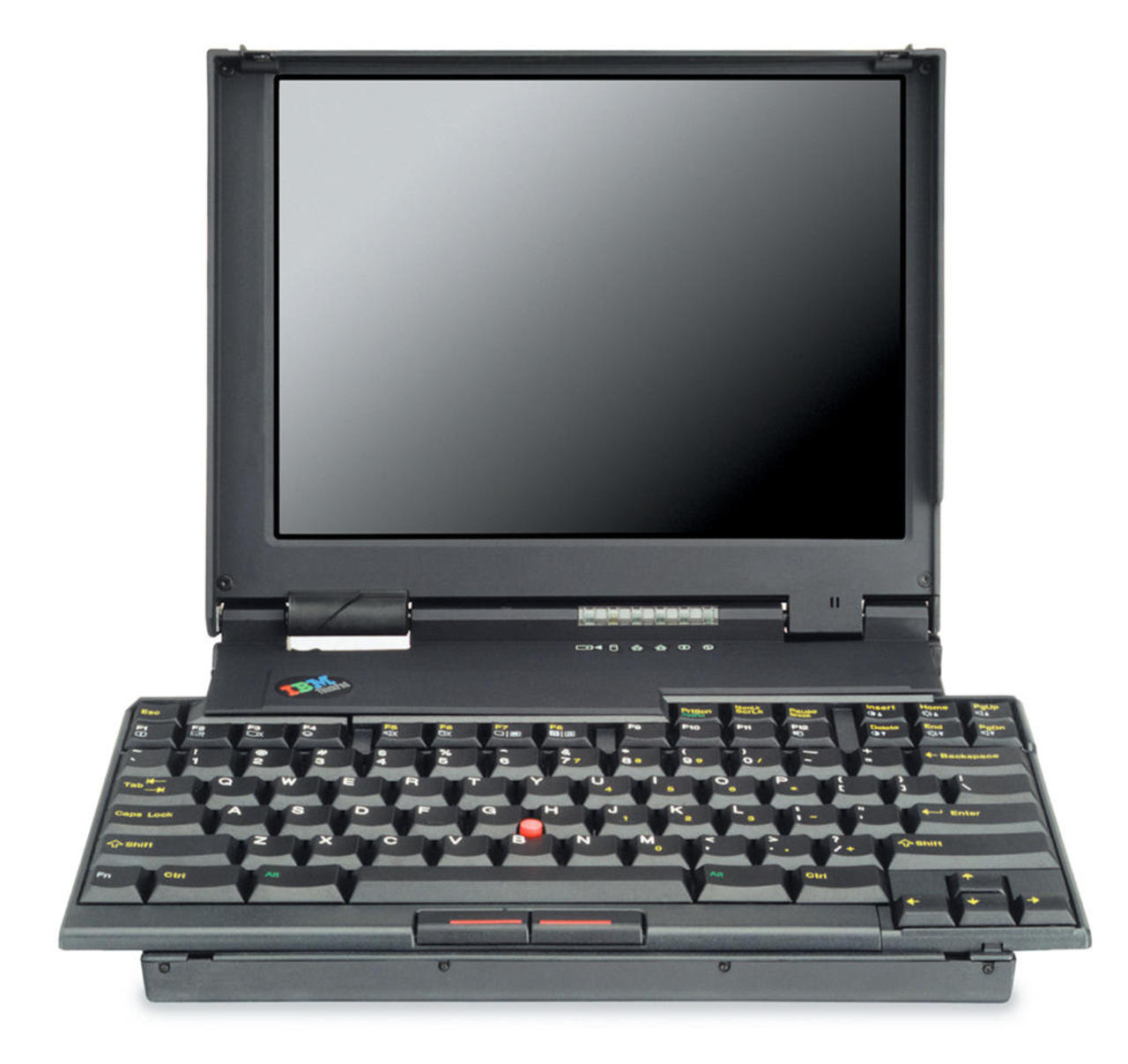

Richard Sapper's IBM Thinkpad: Why is the screen so off centre? Why are the hinges so different? Dieter Rams wouldn't have allowed this.

It is in product design where this high-tech style often shines, as the focus is fully on the legibility of the product. One can't avoid mentioning Richard Sapper here, who's designs, especially the ThinkPad, communicated and exaggerated both the functional details and the mechanisms required for the portable computer which, rather accidentally and conveniently probably enhanced the usability of the machine, but most importantly gave the humble PC a solid, confident, emotional and highly marketable form.

Despite Dyson's claim to the contrary, their products are self-conciously high-tech. They are another example of the over-exubirant celebration of functional matters. This is not a bad thing, high tech design is often a bit babyish and condescending, but the philosophical attitude which puts functionalism at all costs front-and-center is probably the easiest and definitely least compromised way of delivering both utility and 'Big-D Design'. Again though this comes at the cost of attaining the 'Zen' of more sedate versions of modernism.

3) Less and less

While 'Less is More' was an integral part of modernism, from Crystal Palace to Adolf Loos to Mies Van Der Rohe, most pre-seventies modernist architecture of academic regard (Johnson's Glass House and Mies' Farnsworth House excepted) represented a balance between function and reductionism. As the above late-modernist movements of the seventies looked to do more with more, there became something to react against. Tadao Ando's Azuma House (although not as minimalist as we may think) does a lot to represent less as a goal in itself.

Adolf Loos' very clear arguments for less at the turn of the century were focused on reduction of ornament for 'civilisation' but also for reduction in labour. Late modernism's less focuses fully on the aesthetic effect of minimalism - the zen peace of mind associated with lack of distraction, and the communication of luxury through excess space and premium materials.

We also see a turn backwards in minimalism, while the modernists broadly attempted to re-invent forms at any opportunity as part of a forwards thinking desperation, in the effort for 'essentialism', we see in the work of Naoto Fukasawa and Japser Morrison, and in the Architecture of David Chipperfield, a tendency for reduction away from innovative form to more traditional or stereotypical forms. This is part of the goal of minimalism to enhance the anonymity of their design. This does enhance the unobtrusive point that modernism sought to address, but can't be argued to be as forward-thinking as 'proper' modernism.

Sam Hecht of Industrial facility says:

"The less you see the designer's effort in the work, the better - effort should not be a visual commodity, it's simply a means to an end"

But it's also his design that results in extraordinary prices for simple MUJI electronic goods, so if minimalist product design doesn't exemplify the designers effort in an overt visual sense, it does in it's communicating the designer's commitment to the reduction of visual detail, which is even harder.

Minimalism probably does come from an innocent and pure philosophical standpoint, but in today's market economy, it has found it hard to separate itself from the very attractive fashion of less being understood to be more, the very symbols of less becoming a kind of ostentation in themsevelves.

4) The future is bright great?

Brutalism is where this late-modernist argument gets sticky. Does the gritty aesthetic of something like Le Corbusier's Chandigarh parliament building exemplify optimism or does it channel the exact opposite?

I feel like I can use brutalism as an example of modernist optimism exaggerated , if only in the sense that if it was sensible optimism it wouldn't try so hard. Regardless, the subject-matter of brutalist development in the 60s and 70s was nearly always publicly funded and optimistic.

Even in other types of design, such as Kenneth Grange's designs for National Rail, there remained a collective, ambitious longing for proper 'Design' to be a part of the fabric of life. Helvetica wouldn't be the first option for the independent train services of today.

Late modernist design, especially in Britain, usually found it's embodiment in social brutalist developments. As I have previously argued, the aesthetic may derive from a certain contempt for the conditions of the lower-class built environment, but there remains a thread of the architects effort in doing as well as they can. They tried. Postmodernism had a significantly different way of communicating that effort. Brutalism did more than any other visual movement to deliver the optimistic goals of the post-war housing plan, and in all regions across the world it still stands as a symbol of futurist (if naive) belief in the power of concrete and technology to deliver real social change.

***

So here we have explored the world of late-modernist design. In this article, I have argued that late modernism is a movement that spans from the 70s to today that exaggerated modernist tendencies at the cost of the whole goal. There are criticisms of such an approach:

I have only studied the most obvious aspects of 'Big 'D'' design in my approach. therefore, I have given later movements, which benefit from higher historical resolution, the credit of being more variegated and nuanced than older movements. The early 1900's had it's fair share of senseless visual fashions, from Art Deco to Streamline Moderne to Googie , which are irrelevant to contemporary study in the sense that they don't tell the story we are trying to tell. I Ignored such styles in my 'modernism' post and I continue to ignore 'popular' visual styles in my attempt to explain the very superficial movements that define what is considered important 'Design'. People weren't actually buying Richard Sapper lamps in the 70's, they were too busy being distracted by the likes of the Russel Hobbs 'Futura' kettle.

Having said that, Modernism is definitely still a movement that refuses to die, even in this narrow, superficial and misguided sense. The very idea of ideal form, committed, minimal and logical is something that is universally hard to argue against, despite despair-inducing historical (and current) experiences of places like Chandigarh Sector 16C, which prove more than anything that architecture and design needs to be something at least marginally more than less.

The high culture of the 80's had something different to say. This made it's impact in the form of a radical diversion from the modernist trend, a design theory that sought to reject every core of modernism with gay abandon. But perhaps the real damage had already been done by this point. Complexity and Contradiction or otherwise, what we can see from these examples is an architectural model which has reverted totally to retinal representations of the real problems that modernism honestly sought to actually solve. Less, more or anything else, it is clear that by the 70's the academic design practice was only really in the game of designing lamps, chairs, cathedrals and museums; the hard theory finding it hard to interact with the fabric of the real world.