Modernism is (was?) a movement in a wide range of fields, generally thought to have come about properly from about the 1850's. Like all good movements, it began in the spheres of pure philosophy and literary criticism, before trickling down to make a real observable difference in more obvious things like art, architecture and design. I will be focusing on architecture and design, because they are my primary interests. When I refer to 'modernism' from now on, i'm mainly talking about modernism in it's clearest form, which was evident in architecture from about 1910 - 1960, and in product design about the same time.

First, a general visual picture of modernism to set the scene.

Guggenheim Museum, Frank Lloyd Wright; Glass house, Phillip Johnson; Seagram Building, Mies Van Der Rohe

Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier; Braun SK5, Dieter Rams

Ville Radiuse (central Paris plan), Le Corbusier; Looshaus, Adolf Loos; Barcelona chair, Mies van der Rohe

A primary visual analysis of these core pieces of modern design brings to attention primarily two things - a stark lack of ornamentation, and a focus on strict geometries. This much is true, but we can go further. I think we can look at modern design through four 'laws' of modernism;

1) Rules are rules

2) Form follows function

3) Less is more

4) The future is bright

These I believe summarise the commonalities between all pieces of modernist design. The middle two are classic statements, I believe they both came from Mies van der Rohe. Now let's look at these individually.

1) Rules are rules

Modernists love rules. If the design theory can't be summarised into a few bite sized remarks, then is it really a quantifiable design theory? And besides the absolute irony of this being the number one rule in a list of rules, there is a genuine point here.

Modernism came at a time of expanded confidence in rational & deterministic philosophy, and at a time of new scientific discovery. Many designers attempted to 'Discover' the laws of true beauty, and provide a framework for their implication. Most notably, Le Corbusier, who argued very exactly and confidently on the existence of a scientific basis for beauty.

His five points of architecture, combined with his 'modulor' proportion system, seem to have generated most of his earlier works almost automatically. And they are beautiful. Corbusier had done it! he'd worked it out. On to the next problem then? The next problem was urban planning, and the results of that were less inspiring.

The basis of this rule-based approach, I think, was in modernism's fetish for all things Science and Technology. The new generation of designers saw themselves not as the victorian romantic artists, but as new, enlightened technicians. Technical-sounding design theories acted as a personal ego boost and an advertising-style oversimplification.

There is though, a whole lot of good in what we got from these theories. It was in most cases a genuine attempt to understand, in the same way as early medicine or psychology, and their findings act as an easy summary for the beginning student or the interested layman. Acknowledging Rams' 10 principles, with a pinch of salt, is a better place to start from than pretending there is no chance at forming any logical solution - it encourages a certain kind of conclusive thinking and provides a framework for self - assessment.

The Ulm school was perhaps the latest and greatest example as a think-tank for this kind of attitude in design - and although their designs probably did owe more to the intuition than they'd like us to think, the results were a whole lot better than a lot of the critically respected 'high design' we have seen since.

Modernism came at a time of expanded confidence in rational & deterministic philosophy, and at a time of new scientific discovery. Many designers attempted to 'Discover' the laws of true beauty, and provide a framework for their implication. Most notably, Le Corbusier, who argued very exactly and confidently on the existence of a scientific basis for beauty.

"One feels very clearly that the precision required of any act that arouses a superior quality of emotion is based on mathematics" - Le Corbusier, Les Grands courants de la pensé mathématique

"One has to discover the latent geometric law that governs and determines the character of a design" - Le Corbusier, Almancach d'architecture modern

His five points of architecture, combined with his 'modulor' proportion system, seem to have generated most of his earlier works almost automatically. And they are beautiful. Corbusier had done it! he'd worked it out. On to the next problem then? The next problem was urban planning, and the results of that were less inspiring.

A plan for a contemporary city, Le Corbusier

The basis of this rule-based approach, I think, was in modernism's fetish for all things Science and Technology. The new generation of designers saw themselves not as the victorian romantic artists, but as new, enlightened technicians. Technical-sounding design theories acted as a personal ego boost and an advertising-style oversimplification.

There is though, a whole lot of good in what we got from these theories. It was in most cases a genuine attempt to understand, in the same way as early medicine or psychology, and their findings act as an easy summary for the beginning student or the interested layman. Acknowledging Rams' 10 principles, with a pinch of salt, is a better place to start from than pretending there is no chance at forming any logical solution - it encourages a certain kind of conclusive thinking and provides a framework for self - assessment.

The Ulm school was perhaps the latest and greatest example as a think-tank for this kind of attitude in design - and although their designs probably did owe more to the intuition than they'd like us to think, the results were a whole lot better than a lot of the critically respected 'high design' we have seen since.

2) Form follows function

'Form follows function' is presented as something that could be the only rule necessary for design, and a lot of teaching now still follows the same formula. Work out what is required from a product, and the design will find itself. Nothing more. It is the dream of the modernist scientist-designer that things should be this simple.

Some modernist design icons have taken functional utility as their language, for example the above braun T1000, which reassures users that they have full control, confidently placing the will of the machine at their disposal. But this can't be expanded for all products, the SR-71 Blackbird cockpit is an example of extreme functional utility, but it is clear that as products become more complicated, there is required to be a layer of abstraction between use and mechanical response, if they are to be used by the layman.

There is also mechanical utility to be expressed, as in the case of the Wassily chair or the LC4 chaise longue;

But these products are oftentimes at odds with rule number three, 'less is more', that things should be visually unobtrusive. Functional reductionism does not often result in visual reductionism, the more cogs and gears we expose, the less we want to be around a product in many cases. Sometimes these do work well together, an overt display of just enough mechanism can make a product that bit more understandable, as in the case of the SK4/5/55/6 where the useful parts of the of the product were brought out of hiding.

Or in the Angielpoise lamp, where the viewable mechanism gives the design an enhanced understandability , as well as a functional advantage.

But all this rests on a very careful and intuitive balance between what a user needs and what a user wants to see. The interior of an SR-71 Blackbird is also in some way 'functionalist', but ridiculously scary, and requires years of training. The best pieces of design, like the original mini cooper, took serious functional thought and innovation, but then went softly softly on how exactly this informed the aesthetics. A very important part of design then, but not enough on it's own. It is surprising to see that in this case, modernist designers wanted to make their job seem easier than it was.

3) Less is more

Eames house (c.1949) ; Pawson, Palmgren House (2013)

It is within this rule that we can discuss the differences between two different motivations in modernist design. The first I will call 'emancipatory modernism', the second I will call 'aesthetic modernism'. At the turn of the century, Adolf Loos wrote 'Ornament and Crime', and a general study of that work and his others brings about quotes such as-

"Lack of ornament means shorter working hours and consequently higher wages... if I pay as much for a smooth box as for a decorated one, the difference in labor time belongs to the worker. And if there were no ornament at all - a circumstance that will perhaps come true in a few millennia - a man would have to work only four hours instead of eight, for half the work done at present is still for ornamentation" - Adolf Loos

Here, and throughout his work, Loos argues for 'less' on the basis of saved labor, 'civilisation' and increased production. His icons were the bicycle, the steam train and the Thonet chair - things that came about due to new technology, and could now never become retroactively ornamented, since their true, pure function had already shone through.

Loos' enemy, although they were from the same place and both proponents of a new 'style', was Josef Hoffmann, another early modernist architect active in Vienna at the turn of the century. Hoffman had been a part of the Vienna design circle, through Art Nouveau, the Secession, and then the Wiener Werkstätte, and as such was not afraid of being at the helm of a new style. Whereas Adolf Loos wanted to eradicate the meaningless stylistic sways of the middle class, in order to bring about a comfortable home and a well rested worker, it can be argued that all Hoffmann was concerned about was using minimalism and geometry in his designs so he could be a big part of the 'next big thing'.

Loos, Villa Müller (1930) ; Hoffman, Villa Spitzer (1903)

Obviously we are focusing on what has been said about a piece of work and not what the actual motivations were - I think all of these designers tended to be egotistical - but we can see the conception of two attitudes that result in the same prophecy, but perhaps meet it in different ways. Phillip Johnson is perhaps the best example of this, in the fourties, modernism was 'the' style, and stylishly presented it was;

Johnson, Glass House (1949)

But as soon as the next style came knocking, he used that instead, interpreting that in the most superficial of ways.

Johnson, AT&T Building (1984)

The other side of the coin is people who really used 'less is more' as a way of delivering industrial change to the masses, and not as a stylistic exercise. Misfit's Architecure's piece on Earnst May exemplifies this kind of attitude towards design.

"The settlement layouts and the dwellings and their spaces were highly functional. This was not the pursuit of functionalism as a style, but a means of not wasting space and the building materials to enclose it."

So yes, less can be more, especially when prepared with some genuine social thought and an attitude for function, as all the best examples of modernism were. The fact that less isn't always more, and isn't exclusively the only objective, is the focus of many works including Venturi's Complexity and Contradiction in Modern Architecture, but i'm not sure wether less is exclusively a bore either.

4) The future is bright

The final thing we need to consider about modernism is that it was in full force in the 20's, 30's and 40's. Unlike other movements like Dada, which swelled in the despair of war, or Constructivism, which actively promoted the hard socialism of the soviet regime, modernism existed mainly as optimistic movement, challenged by the industrial revolution to deliver technocratic change to the everyday person.

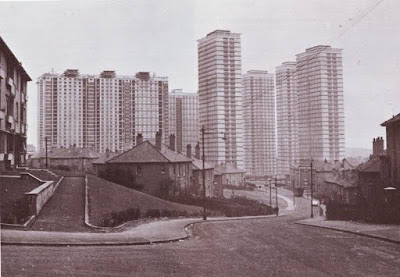

If we take Glasgow as an example, modernism took the poorest in society from this;

Carnoustie Street tenements, 1930s

Cramped, dated and unsanitary tenement flats, to a new vision of the future; steel framed high rise towers, social provisions, community facilities, the skyscraper in the park;

We all know where this story ends, and have seen it in cities across the world - demolition. We can generally agree that these were failed projects; due to lack of maintenance, lack of council ambition, or perhaps just because the modernists were just straight up wrong.

And wrong they were, but it can be argued that perhaps that malicious they were not. Housing schemes, new household products, the automobile, the steam engine, the electricity grid; these are all products of a movement that genuinely, in most cases, wanted to confidently build a new society. A designer at the turn of the century could be forgiven for thinking that the growing bubble of technological development was not inevitably going to become the only answer they needed. This attitude is most clearly exemplified in the crazily ambitious and futuristic plans by Buckminster Fuller.

Buckminster Fuller, Expo 67

In it's ambition for wide, technocratic change, the modernist sometimes flirted with such abhorrences as Fascism - Le Corbusier was famous for courting the Vichy regime in France during WWII - but it was also modernism that was ousted from Hitler's Nazi Germany in the 1930's for being too socially progressive, this is why 1930's Tel Aviv looks like a bauhaus utopia.

So while we can't give a definitive political side to modernism, I think we can find that for better or for worse, it was a movement that was wholly, ambitiously and blindly in favour of sweeping technological change for the better. And whilst in many cases it failed dramatically to live up to it's grand promises, it is perhaps sad that we have never had the same optimism for the power of design since.

***

Here I have critically presented modernism as a set of rules, that when taken together describe much of any modernist work. The rigidity of this presentation style reflects the rigidity of the modernist regime, and in it's rigidity and blind progressive attitude it is clear how it began to get a bad reputation in the later half of the 20th century. If however we see it not as 'Four rules of modernism';

1) Rules are rules

2) Form follows function

3) Less is more

4) The future is bright

but more gently as what I will call four principles of modernism;

objectivity, functionality, neutrality & optimism

we can maybe began to see modernism more softly as a force for genuine good.

I think generally though, modernism is tarnished by the arrogance and egotism of many of it's proponents. In their failure - commonly iconified by the destruction of the Pruitt–Igoe complex in 1972 - we can learn that while objectivity, functionality, neutrality & optimism seem like good principles for any design project; that we must work towards good design thinking genuinely about the end user and their needs, and not towards merely proving ourselves as 'right'. History may come back to prove us wrong.